How to Talk About Valuation When a VC Asks

One of the hardest things about the fund-raising process for entrepreneurs is that you’re trying to raise money from people who have “asymmetric information.” VC firms see thousands of deals and have a refined sense of how the market is valuing deals because they get price signals across all of these deals. As an entrepreneur it can feel as intimidating as going to buy a car where the dealer knows the price of every make & model of a car and you’re guessing at how much to pay.

I thought I’d write a post about how to talk about valuation at a startup and give you some sense of what might be on the mind of the person considering funding you. Of course, unlike cars there is no direct comparison across each startup so these are just some general guidelines to try and even the information field.

What was the post money on your last round (and how much capital have you raised)?

It’s not uncommon for a VC to ask you how much capital you’ve raised and what the post-money valuation was on your last round. I know that some founders feel uncomfortable with this as though they might somehow be sharing something so confidential that it ultimately hurts you. These are straightforward questions, the answers will have no bearing on your ultimate success and if you want to know the truth most VCs have access to databases like Pitchbook that have all of this information anyways.

So why does a VC ask you?

In the first place they’re looking for “fit” with their firm. If you’re talking with a typical Seed/A/B round firm they often have ownership targets in the company in which they invest. Since they have limited capital and limited time availability they often try to make concentrated investments across companies in which they have the highest conviction. If a firm typically invests $5 million in its first check and its target is to own 20% or more that means that most if its deals are in the $15–20 million pre-money range. If you’re raising at $40 million pre then you might be out of their strike zone.

Many VCs will have a distribution curve where they’ll do a small number of early-stage deals (say $1.5–3 million invested at a $6–10m pre-money), a larger number of “down the fairway” deals ($4–5 million at a $15–25 million pre) and a few later-stage deals (say $8–10 million at a $30–40 million pre).Of course there are smaller funds that are more price sensitive and want to invest earlier and later stage funds with more capital to deploy and write larger checks a higher prices so understanding what is that VC’s “norm” is important.

A second thing a VC may be trying to determine is whether your last-round valuation was significantly over-priced. Of course valuation is in the eye of the beholder but if that VC thinks your last round valuation was way too high then he or she is more likely to politely pass rather than try and talk down your valuation now. VCs hate “down rounds” and many don’t even like “flat rounds.” There are some simple reasons. For starters, VCs don’t like to piss off a bunch of your previous-round VCs because they’ll likely have to work with them in other deals. They also don’t want to become a shareholder in a company where every other shareholder starts by being annoyed with them.

But there is also another very rational reason. If a VC prices a flat or down round it means that management teams are often taking too much dilution. Every VC knows that talented founders or executives who don’t own enough of the company or perceive they will have enough upside will eventually start thinking about their next company and are less likely to stick around. So a VC doesn’t want to price a deal in which the founder feels aggrieved from day one but takes your money anyway because he or she doesn’t have a choice.

Every VC has a story where they did the flat round anyways and the founder said, “I really don’t mind! I know our last round valuation was too high.” In nearly 100% of those cases the founder expresses his or her frustration a year later (and 2 years later and 4 years later). The memory isn’t “boy, you stepped in at a time where we were having a tough time getting other VCs to see the value in our company — thank you!” it is more likely a softer version of “you took advantage of us when we had no other options.”

It is this muscle memory that makes the VC want to pass on the next down or flat round. In a market where there is always another great deal to evaluate, why sign up to one where you know there are going to be bruised egos from the get go?

The “how much have you raised?” question is usually a VC trying to determine whether you’ve been capital efficient with the funds you’ve raised to date. If you’ve raised large amounts of money and can’t show much progress obviously you’ve got a tougher time to explain the past then if you’ve been frugal and over-achieved.

My advice to founders on the questions of “how much did you raise in the last round?” and “what was the post-money valuation of your last round?” is to start with just the data. If you don’t perceive that you have any potential “issues” (raised too much, price too high) then this should be a non event. If you are aware you may have some issues or if you are constantly getting feedback that you may have issues then it’s a smart strategy for you to develop a set of talking points to get in front of the issue when asked.

What expectations do you have about valuation?

It is not uncommon for a VC to ask about your price expectations in this fund raising process. It’s a legitimate question as the VC is in “price discovery” mode and wants a sense whether you’re in his or her valuation range.

It’s a tough dance but I would suggest the following:

- In most cases don’t name an actual price

- Your job is to “anchor” by giving the VC a general range without saying it. Call this “price signaling.”

- Turn the tables on the VC by politely saying, “given you must have a sense of our general valuation, how do you feel the market is pricing rounds like ours these days? After all — we only raise once every 1–2 years!”

Why shouldn’t most founders just name a price? For starters, it’s the job of the “buyer” to name price and you don’t want to name your valuation if it ends up being lower than the VC would have paid or a price too high they the VC simply pulls out of the process.

So then why anchor? If you don’t give signals to a VC of what your general expectations are it’s hard for them to know whether you have realistic expectations relative to their perceived value of you and you want to keep them in the process rather than just having them pull out based on what they THINK you might want on valuation.

Any great negotiation starts by anchoring the other party’s expectations and then testing their reaction.

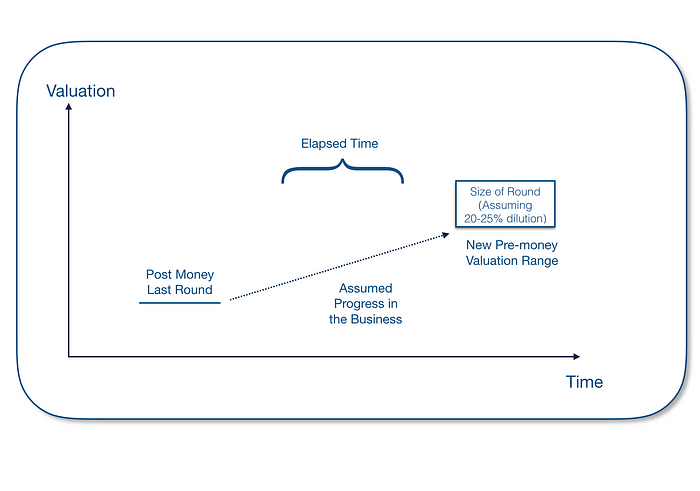

How you talk about valuation will of course depend on how well your business is performing and how much demand you have from other investors. If I leave out the immediate “up and to the right” companies and talk about most others who have made good progress since the last funding but the next round isn’t a slam dunk, you might consider something like if asked about your expectations:

- We closed our last round at a $17 million post-money valuation and we had raised $3.5 million.

- We closed it 20 months ago and we feel like we’ve made great progress

- We’re hoping to raise $5–7 million in this round

- We know roughly how VCs price rounds and we think we’ll likely be within the normal range of expectations

- But obviously we’re going to let the market tell us what the right valuation is. We only raise every 2 years so the market will have a better feel for it than we will

- We’re optimizing for the best long-term fit for a VC and who we think will help us create the most value. We’re not optimizing for the highest price. But obviously we want a fair price.

- How do you generally think about valuation for a company at our stage? (this is seeking feedback / testing your reponse)

Here you’ve set a bunch of signals without naming your price. What a VC heard was:

- The price has to be higher than $17 million, which was the last round. It was 20 months ago and the founder clearly told me she has made great process (code words for higher price expected)

- She is raising $5–7 million and knows the range of valuations for this amount. If I assume 20–25% dilution that implies a price of between $20–28 million pre-money valuation ($25-$35m post-money). Maybe she wants slightly higher but she certainly won’t want lower.

- She has told me she’s not trying to shop this to the highest price. I’m not so naive as to completely believe that — every entrepreneur will go for the highest reasonable price with a VC they like so I at least need to put my best foot forward. But if I’m in the ballpark of fair she won’t game me and push for the highest price as the only part of her decision.

Are your existing investors participating in this round?

This is a delicate dance as well. Each new investor knows that the people who have the MOST asymmetric information on your performance are the previous round investors. They not only know all of your data and how you’re doing relative to competition, but they also have a good view on how well your management team is performing together and whether you’re a good leader.

On the one hand a new potential investor will want to know that your existing investors are willing to continue to invest heavily in this round and at the same price that they are paying, on the other hand they want to invest enough of the round to hit their ownership targets and may not want existing investors to take their full prorata investments.

Before raising capital you need to have a conversation with your existing investors to get a sense on what they’re thinking or at a minimum you better have an intuitive feel for it. Assuming that most of your existing investors are supportive but want a new outside lead, I recommend answering this something like this:

- Our existing investors of course want to participate in this round. They will likely want to do their prorata investments — some might even want slightly more.

- I know that new firms have ownership targets. I feel confident I can meet these. If it becomes sensitive between a new investors needs and previous investors — I’m obviously not going to tell my investors they can’t participate but I feel confident I can work with them to keep the sizes of their checks reasonable.

What a VC hears when you say this:

- My existing investors are supportive. I will eventually call them anyways to confirm but I can continue my investment assuming they are supportive

- In the future if we raise a larger round this entrepreneur won’t try to screw me by forcing me not to take my prorata rights because they weren’t throwing existing investors under the bus with me

- This entrepreneur is sophisticated enough to know that fund-raising is dance in which I need to meet the needs of both new investors and of previous investors. They will work with me so I can get close to my ownership targets.

When SHOULD you name a valuation expectation?

There are some types of rounds where just naming price might be a better option.

- Strategics (ie industry investors vs. VCs). For some reason many strategic investors don’t like to lead rounds and they don’t like to name a price. This isn’t true of all strategics but it is true for many of them — particularly those who don’t have a long history in VC. Having a price helps them to evaluate the deal better. Often they’re much better at a “yes/no” decision than naming a price. If you name your valuation you sometimes have to give them rationale on how similar companies are valued so they can justify their internal case. Knowing that other institutional investors (including your insiders) are paying the same price as them in this round helps.

- Many investors. When you are raising for 8–10 new sources vs. 1–2 sometimes it’s easier just to name price. One reason you might be raising from so many sources is that you haven’t found it easy to find a strong lead investor (for say $20 million) but many sources are willing to write you smaller checks (of say $2–3 million each). Many investors can also be the opposite situation where you’re so successful that everybody wants to invest. In either case, having a price target can help you get momentum.

Turning the information tables

Final point. If done in the right way, each VC meeting can be a great opportunity for you to get feedback on how investors are seeing market valuations in the time that you’re raising (valuations change based on the overall funding economy) and also a chance to hear about how the VCs think about your valuation and/or let you know whether or not you have any perceived problems.

You might politely ask questions like:

- Does your firm have a target ownership range?

- Do you typically like to lead and do you ever follow?

- Are there firms you like to co-invest with?

- Does our fund-raising size sound reasonable to you?

- Are there any valuation concerns you might have that we can address now?

Your goal in forming questions is to get signaling back from the VC. Remember that fund-raising is a two-way process and you have every right to ask questions that help orient you just as a good VC will ask questions of you.

Want to read more?

This is part of a series I’ve been writing on fund raising. If you’ve enjoyed or learned please email to a friend or share through social. And you can follow me on Twitter or on Snap and receive my newsletter direct to you email box here:

So far I’ve covered:

- Why you hear “no” very quickly a fund raising process?

- How to plan a fund raise before you even start

- The importance of in-person meetings and re-engagement in your process

- How to manage your psychology during a difficult raise

- How many VCs should you meet? And how do you prioritize your time?

- Why it’s better to send a deck rather than a link to investors

- Why you shouldn’t send investors all your data too early in the process

- Why taking some risks in fund raising and being willing to hear “no” can actually help you get to “yes”

- Why confidence is so important in fund raising

- Why it’s important to meet more partners at a firm than just your sponsoring partner

- How much to raise and how long should your money last?